11 Famous cycling climbs in France to add to your bucket list

The high mountain passes were first featured in the Tour de France in 1910. Back then riders were set the unenviable task of riding extremely long distances on heavy steel bikes, with wooden wheels on unpaved roads. This set the stage for some amazing cycling folklore to be written. Now, each year many fans of the sport travel to France looking to pit themselves up against the steep gradients of the mountain roads. They are keen to see what it is like to ride these icons and cherish the challenge of reaching the summit. We have put a list together of eleven climbs in total that we think every cyclist should try to ride. This includes eight of the most iconic climbs to ride in France as well as three climbs we have identified as icons of the future.

Without a doubt, France is home to some of cycling’s most iconic climbs. We’ve procured our own ‘hit list’ detailing 11 climbs we believe need to be on every cyclist’s bucket list! How many have you ridden?

1. Col du Tourmalet

“Crossed Tourmalet stop. Very good road stop. Perfectly feasible”

Telegram sent from Alphonse Steinès to Henri Desgranges declaring the Tourmalet Pass suitable for inclusion in the 1910 edition of the Tour de France (even though he didn’t make it to the top himself!)

Most featured climb in the Tour de France

During the early editions of the Tour de France, race organizers sought out challenging routes where ideally only one person would be able to finish the course. So it was that they looked towards the Pyrenees and including steep mountains for the first time. A scout for the L’Equipe Newspaper was sent out to determine whether the roads leading up and over the mountain passes were navigable by two wheels. Despite not being able to reach the summit of the Col du Tourmalet himself due to a mix of bad weather and road conditions, a telegram was sent indicating it was totally feasible for cyclists. So it was that in 1910 the Col du Tourmalet was included in the race. Since then it has been featured 87 times and was last used in the 2021 edition of the race.

Tour de France pedigree

Octave Lapize took the honor of being the first rider over the top of Col du Tourmalet in 1910. This was quite a feat and saw the race pass over 2000m in elevation. At the summit, a giant statue of the rider pays tribute to his efforts. It is hard to comprehend just how difficult the ascent to the top would have been, considering the road was unpaved, the bikes were far removed from the lightweight, modern, carbon fiber frames of today. The cafe at the summit proudly displays the old bikes used in these earlier editions of the race and they are well worth looking at.

Of course, the challenge of summiting the Col du Tourmalet is only half the story for these early editions of the race, descending on these bikes was perhaps even harder. The story of Eugene Christoff is another famous tale of woe on the Col du Tourmalet where the fork on his bike broke during the descent. He managed to fix it at Saint Marie de Campan, a village at the base of the climb, only to be handed a time penalty by the race organizers. He was deemed to have accepted outside assistance due to needing a person to operate the bellows while he welded the frame back together!

Two approaches to reach the summit

There are two approaches to the climb of the Col du Tourmalet. Both are classified as Hors Categorie and have a similar distance and an average gradient of 7.4%. An amateur cyclist will do well to reach the top in 1 hour 45mins and each year thousands take on the challenge of riding to the summit. As with many famous Tour de France climbs, there are signs every kilometer of the roadside indicating the gradient of the next kilometer and the distance left to reach the summit. You will either love or hate these markers depending on how your legs feel on the day. You will also see paint on the road, leftover from spectators of previous editions of the Tour de France.

One of the highest paved mountain passes in the Pyrenees

With an altitude of 2115m, for many years the Col du Tourmalet also lay claim to being the highest paved mountain pass (through road) in the Pyrenees. This was overtaken in 201 8 when the road to the Col du Portet was paved in preparation for the Tour’s arrival. Regardless, it is a climb synonymous with the famous race and arguably one of the most well-known cycling climbs in the world.

Check out our Pyrenees Destination Guide page where you will discover more details about the Col du Tourmalet climb as well as other rides in the area.

Above: Bikes like this one were used in 1910, for the first ride up over the Tourmalet.

Tourmalet Climb (eastern approach)

Length: 17.2km / 10.7mi

Average Gradient: 7.4%

Starting Town: Sainte-Marie-de-Campan

Elevation Gain: 1268m / 4,160ft

Height at Summit: 2,115m / 6,939ft

Tourmalet Climb (western approach)

Length: 19km / 11.8mi

Average Gradient: 7.4%

Starting Town: Luz Saint Sauveur

Elevation Gain: 1,404m / 4,606ft

Height at Summit: 2,115m / 6,939ft

2. Alpe d’Huez

” From the first edition, shown on live television, the Alpe d’Huez definitively transformed the way the Grande Boucle ran. No other stage has had such drama. With its 21 bends, its gradient, and the number of spectators, it is a climb in the style of Hollywood.”

Jacques Augendre, L’Equipe

The most famous 21 hairpin bends in France

Had it not been for a consortium of business owners looking to secure some extra marketing for their ski station, the climb of Alpe d’Huez may not be so well known. They petitioned the Tour de France race organizers and persuaded them to host the first-ever mountain top stage finish of the race. They were successful and the climb made its first appearance in 1952. The stage was won by Italian Fausto Coppi. Since its first use, Alpe d’Huez is arguably one of cycling’s most iconic climbs in the world.

The 21 hairpin bends of the Alpe are a regular feature of the Tour de France. Thousands of cyclists descend on the village of Bourg d’Oisans each year with the view of riding up this famous mountain road. Each of the 21 bends is numbered and also has a nameplate that signifies a Tour de France stage winner on the mountain. Because the climb has featured in so many editions of the race many of these nameplates carry the name of more than one rider.

Dutch Mountain

Due to the number of Dutch stage winners, the climb has also been nicknamed ‘Dutch Mountain’ and hairpin bend no 7 is now known as Dutch Corner. It is here that fans from the Netherlands all place themselves days before the tour arrives, pumping out techno dance music and creating a party atmosphere. In fact, whether it is at Dutch Corner, or somewhere else on the climb, spectating a stage of the tour roadside on Alpe d’Huez should be on every cyclist’s bucket list. It has been estimated that there can be over a million fans spread out on the climb, cheering on the riders.

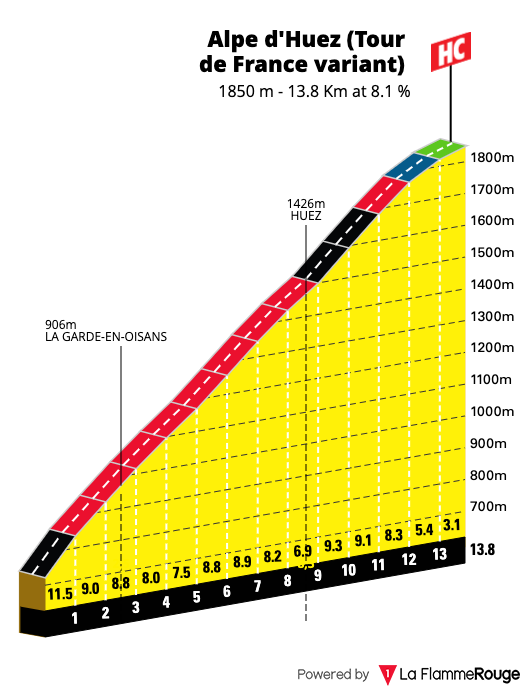

The climb itself is 13.8kms long with an average gradient of 8.1% and is classified as Hors Categorie. The steepest gradients come in the first kilometer of the climb where it rarely goes below 10%. You soon realize that with each hairpin comes some respite as the road flattens off allowing you a small amount of recovery before it ramps up once more. Whilst the climb officially ends at the ski village, the Tour de France stage always finishes a little further up the mountain so be aware of this if riding the climb yourself.

Check out our dedicated page on Alpe d’Huez for more details about the climb as well as other rides in the area.

Alpe d’Huez Climb

Length: 13.8km / 8.6mi

Average Gradient: 8.1%

Starting Town: Bourg d’Oisans

Elevation Gain: 1,120m / 3,675ft

Height at Summit: 1,850m / 6,070ft

3. Col d’Aubisque

” Vous étes des assassins! Oui des assasins.”

Oscar Lapize shouted to the organizers of the 1910 Tour de France as he climbed Col d’Aubisque

A Pyrenean great

The Col d’Aubisque is a real icon of the Pyrenees. It was first used in the 1910 edition of the race and was the final Hors Categorie climb on stage 10. Reading the details of that stage it is no wonder that Octave Lapize famously shouted towards the race organizers that they were assassins whilst climbing the Aubisque. The stage was 326kms in length and included no less than four high mountain passes. Most riders were reduced to walking the climbs, on bikes that were really not equipped to take on the steep gradients. Throw in the fact the roads then were rough, gravel tracks and not the smooth tarmac of today. There is no question the feats of the riders during these early editions of the Tour were on another level of endurance and strength. Since 1910 the climb of the Aubisque has been a regular inclusion in the Tour de France – second only to the Col du Tourmalet in terms of appearances in the race with a total of 74. Due to its proximity to Spain, it also featured in the 2014 edition of the Vuelta a España.

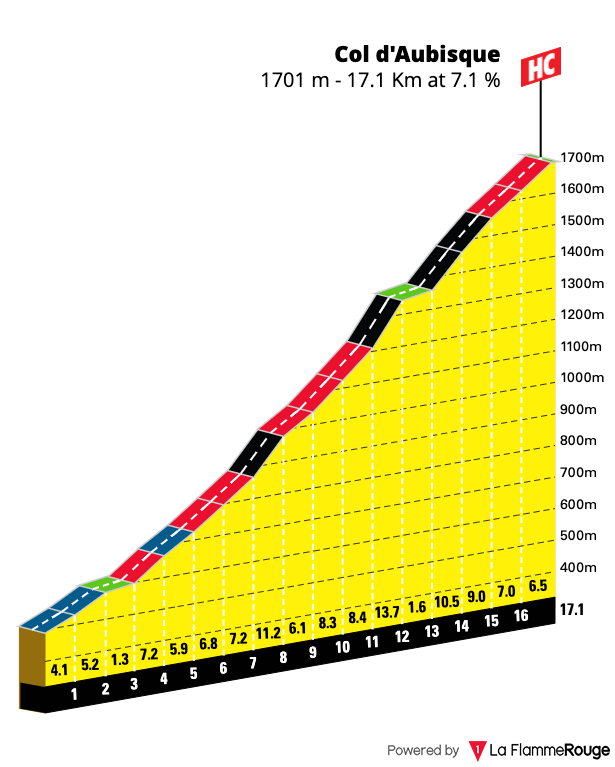

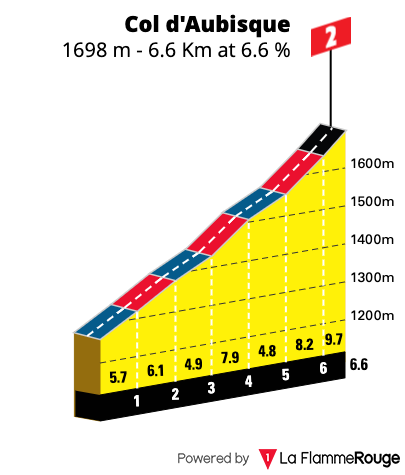

Two ways to the summit

There are two approaches to the Aubisque. From the west, the climb begins in the town of Laruns and is 16kms / 10mi in length with an average of 7.2%. This is the steeper of the two approaches and the section past the small village of Eaux Bonnes to the ski resort at Gourettes sees the most challenging gradients. From the East, the climb is 30kms in length beginning in Argeles Gazost. This approach also takes in the pass of the Col du Soulor and the stunning balcony road of the Cirque du Litor. From this point, the climb is just over 7.5kms / 4mi in length with an average gradient of 4.6% Another feature of the climb here – as is the case with many other cols in the Pyrenees is the roaming livestock. It is very common to see sheep, cattle, horses, and even donkeys roaming free along the road.

Stunning vistas mixed with mountain weather

The weather can also close in quite regularly over the Aubisque and thick fog is known to enshroud the mountain. This makes visibility a challenge but also adds to the mystique of the climb itself. On a clear day, there are not many places in the Pyrenees that are more scenic. Huge rocky peaks dominate, towering over the lower slopes. You can also see directly across the vast chasm which leads onto the northern side of the Soulor Pass.

Dramatic Tour de France mountain rescue

The dramatic cliff road of the Cirque du Litor really is perched on the very edge of the mountain. Rocky, vertical slopes branch upwards and downwards and if you are prone to bouts of vertigo then perhaps don’t look over the edge! It is this section of road which famously saw Wim Van Este overshoot a bend and plunge off the mountain, landing some 70metres further down the slopes. It was the 1951 Tour de France and the Dutch rider was in the yellow jersey, having to chase hard to close down a gap. A mistimed corner saw him fly off the mountain. To rescue him the team tied all their tubular tires together to form a type of rope. By doing so the tires became stretched and the team had no option but to withdraw from the race. Now there is a commemorative plaque to Wim van Este on the very spot where he left the roadside. You can see archive race footage of the rescue here.

At the summit of the Aubisque are three large steel bikes each in the colors of the Tour de France race jerseys. A ride up the mountain isn’t complete without a photo taken here and in Summer this spot is a hive of cyclists who themselves have taken on the challenge of cycling the col. At an elevation of 1709m / 5607ft, it may not be the highest mountain pass, but certainly, if you find yourself in the Pyrenees, the climb of the Aubisque is a must.

Check out our dedicated cycling guide for the Col d’Aubisque for more details about the climb as well as other rides in the area.

Col d’Aubisque Climb (western approach)

Length: 17.1km / 10.6mi

Average Gradient: 7.1%

Starting Town: Laruns

Elevation Gain: 1,185m / 3,885ft

Height at Summit: 1,709m / 5,607ft

Col d’Aubisque Climb (eastern approach)

Length: 6.6km / 4.1mi

Average Gradient: 6.6%

Starting Point: Cirque du Litor

Elevation Gain: 235m / 771ft

Height at Summit: 1,709m / 5,607ft

4. Mont Ventoux

“From there it was 10km of forest, no switchbacks, just trees, at 10%…for the first time in my life, my computer was on single numbers, I saw 8 and 9km/h.”

Eros Poli recounting the climb of Mont Ventoux on his breakaway stage win in 1994

The Giant of Provence

Mont Ventoux can be seen looming large over the landscape of Provence. Indeed, the mountain is visible from quite a distance and is well recognized as being the largest peak in the Vaucluse region of France. To the unknowing eye, It can appear to be snowcapped however this is the illusion that the barren landscape at the top of the climb gives out. Once covered in trees, these were felled many centuries ago to build ships. Due to the high winds which the mountain is often plagued by, the soil has eroded and the landscape has been left bare. This unique characteristic certainly adds to the mythical charm of the climb itself.

Tour de France history

Mont Ventoux was first included in the Tour de France in 1951 and has been a regular inclusion since. It has been the scene for a mountaintop finish on no less than 10 occasions and the Tour is set to cross the summit not once but twice in 2021. While there have been many famous cycling stories written on the slopes of Ventoux, it is the tragic tale of Tom Simpson which is most well known. In 1957, the British rider was within 1km of the summit, before he started weaving along the road. Suffering from the effects of heat exhaustion which was amplified by the use of amphetamines, he collapsed on the roadside and sadly passed away. There is a memorial to the fallen rider and now many cycling fans leave small mementos there as a sign of respect.

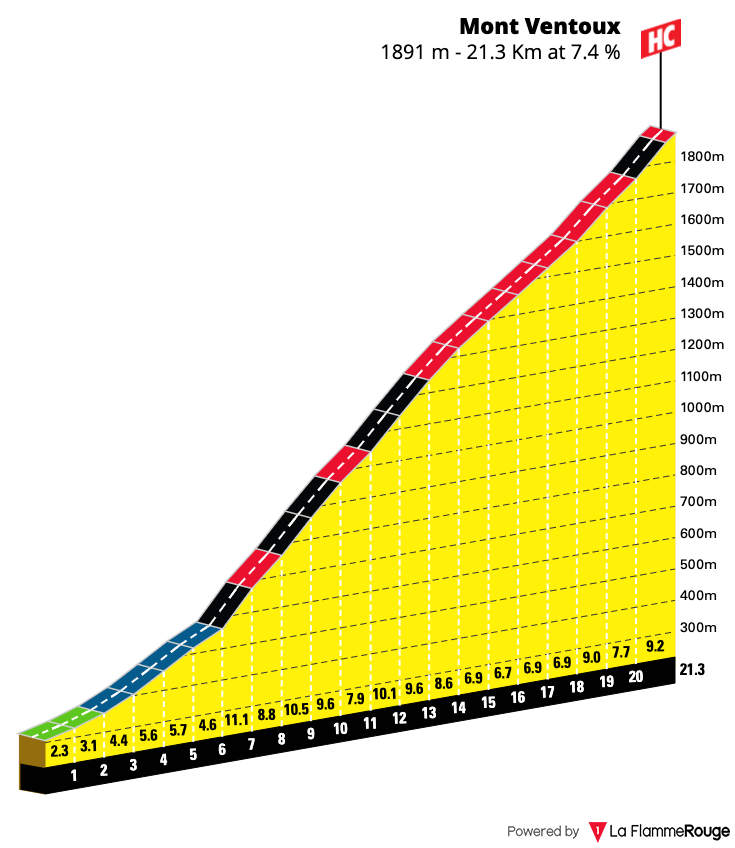

There are three approaches to the climb which lead to the summit. The most well-known of these is the approach from the small village of Bédoin and this is the side which the Tour chooses to use. From here an amateur cyclist can expect to take anywhere from 90mins to 2 and a half hours to reach the top. The climb is 21.3kms long with an average gradient of 7.4%. A long section through the forest will see your legs turning pedals over double-digit gradients for what will seem an eternity. The heat of summer will only add to the challenge.

Windy Mountain

Six kilometers from the summit the small building of Chalet Reynard appears and the barren, rocky landscape begins to dominate. Out of the cover of the trees, strong winds are the next adversary to face. Indeed, the name Ventoux is the French term meaning ‘windy’ and it is very apt. Some of the strongest winds on earth have been recorded here and it is reported that the windspeed on Ventoux peaks over 90kms per hour on average 2 out of every 3 days. Due to high winds, the stage finish in 2016 had to be lowered from the summit to Chalet Reynard as it was too dangerous for riders and spectators to be higher up the mountain. This was the stage that saw Chris Froome famously reduced to running towards the finish line due to a mishap with a race motorcycle.

Ventoux Cyclosportives

It is estimated that annually over 120,000 cyclists take to the slopes of Mont Ventoux with the view of riding to the summit. There are also numerous cyclosportives based around the climb itself including the Hautes Route Ventoux which climbs all three approaches over the course of three stages. If you are after a real challenge then perhaps the Club des Cinglés du Mont Ventoux is for you. This involves riding all three roads to the summit in just one day. In doing so you can then be inaugurated into the exclusive club. You can read more about the rules of this challenge here.

Discover more about the cycling on offer in the Luberon and Provence region at our dedicated destination guide. You will also find more information about tackling the Mont Ventoux climb for yourself.

Mont Ventoux Climb (Bédoin approach)

Length: 21.3km / 13.2mi

Average Gradient: 7.4%

Starting Point: Bedoin

Elevation Gain: 1,617m / 5,305ft

Height at Summit: 1,909m / 6,263ft

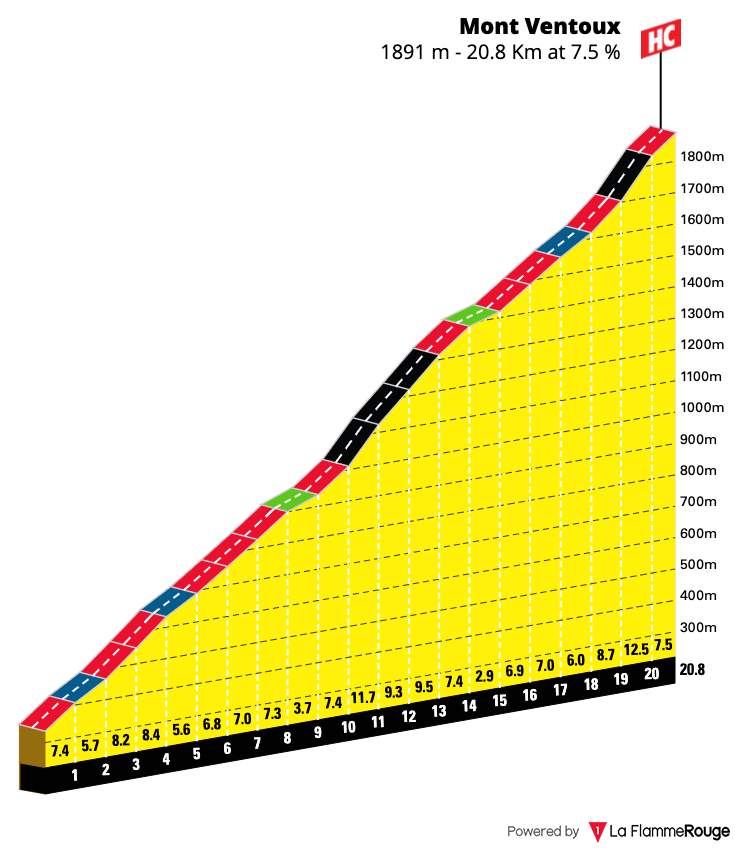

Mont Ventoux Climb (Malaucène approach)

Length: 20.8km / 12.9mi

Average Gradient: 7.5%

Starting Point: Malaucène

Elevation Gain: 1,579m / 5,150ft

Height at Summit: 1,909m / 6,263ft

Mont Ventoux Climb (Sault approach)

Length: 24.5km / 15.2mi

Average Gradient: 4.9%

Starting Point: Sault

Elevation Gain: 1,210m / 3,970t

Height at Summit: 1,911m / 5,607ft

5. Col du Peyresourde

“I thought over the top let me just give it a go and see what I can do on the descent – I’ll see if I can catch someone out. It was real old-school bike racing!”

Chris Froome after completing a thrilling descent on the Col du Peyresourde to take the yellow jersey in 2016.

Anthospace, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

A Tour de France regular since 1910

The Col du Peyresourde was first featured in the 1910 edition of the Tour de France on stage 10. This was the first introduction of the high mountains to the race. The stage was nicknamed the ‘circle of death’ and over 326km it would entail the riders traveling from Bagnéres-du-Luchon to Bayonne, over no less than four high mountain passes. The Peyresourde was the first mountain the riders had to tackle on that day. This stage was so hard that in response to protests by riders when the route was revealed, organizers chose to introduce the concept of a ‘Broom Wagon’ follow car. For the tour organizers, this would be a way to stop the riders from cheating and they also agreed that any riders who used the Broom Wagon during stage 10, would be allowed to continue with the race on stage 11.

Accessible year-round

The Peyresourde is a Category One climb and whilst it may not be as steep as others such as the Tourmalet and Aubisque, it nonetheless will provide you with a challenge. Since its first inclusion in the race in 1910, it has been used in the Tour de France on 68 occasions, making it one of the icons of the Pyrenees. The other unique element of the Peyresourde climb is that it is generally accessible year-round – when many of the higher mountain passes are closed during the winter months.

Climb variation includes the summit of Peyragudes

Often the Col du Peyresourde has been used in the Tour de France as a ‘lead-in’ climb, an appetizer for harder climbs to come on the stage. In recent years an extension to the climb has even been added – taking riders higher up the mountain, to the ski resort of Peyragudes. Adding this extra 4km section to the Peyresourde climb certainly makes it a much harder task. Whilst the regular gradient of the Peyresourde lends itself to be an ‘easier’ climb that may not put you in the red, it also means the descent can be a dream to those who enjoy the thrill of the downhills. Indeed, in 2016 Chris Froome attacked over the top of the Peyresourde and managed to increase his lead over the peloton whilst showing off a very aerodynamic top tube pedaling style.

Two ways to reach the Peyresourde summit

There are two approaches to the climb, with the eastern approach from Bagnères-du-Luchon being the tougher option. The length will take its toll and some steeper sections – especially at the beginning of the climb will prove to be challenging. As you come closer to the top the true magic of the climb reveals itself, with the mountain seeming to open up wide with a set of switchbacks taking you to the summit. Once there, spare a thought for those Tour de France riders in 1910, who after getting to this point still had three mountain passes to climb!

Check out our Pyrenees destination guide for more details about the Col du Peyresourde climb as well as other rides in the area.

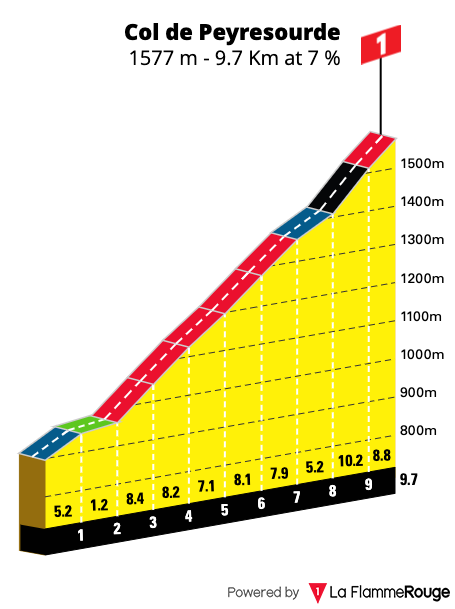

Col du Peyresourde Climb (eastern approach)

Length: 15.3km / 19.5mi

Average Gradient: 6.1%

Starting Point: Bagnères-de-Luchon

Elevation Gain: 939m / 3,081t

Height at Summit: 1,569m / 5,148ft

Col du Peyresourde Climb (western approach)

Length: 8.3km / 5.2mi

Average Gradient: 7.6%

Starting Point: Armanteule

Elevation Gain: 629m / 2,064t

Height at Summit: 1,569m / 5,148ft

6. Col de la Madone

“It’s a strange feeling we have after doing it. We feel slightly guilty and a bit sheepish, I turn to Richie: ‘We can’t tell people about this.’ We don’t want to go there.”

Chris Froomes’ thoughts after setting a record time of 30mins 09seconds on the Col de la Madone

Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

A testing ground to gauge good form

The Col de la Madone has surprisingly never featured as a climb in the Tour de France. Yet it is one of the most famous climbs in France. The Trek brand even named its flagship road bike model after it. So what makes this climb an icon and so famous? Well, it has a lot to do with a certain Lance Armstrong who used the climb as a testing ground to see how his form was prior to the Tour de France. A good time set on the climb of the Madone would be able to give him an insight into how ‘well’ he was going.

How much time will it take to climb the Madone?

Many other professional riders since Armstrong have also chosen the Madone as their testing ground. This probably has more to do with the fact many pro riders live in Monaco during the off-season where even in the winter months they are able to train outdoors and enjoy warmer temperatures. So what is a good time up the Madone? Whilst an amateur cyclist who rides regularly can hope to set a time of approximately 45mins up the 12.9km climb, for a professional cyclist a time closer to the thirty-minute mark is a sign that they are in peak condition. During a training ride In 2015, the Australian rider Ritchie Porte set the fastest time of 29mins 40seconds.

Scenic climb with coastal views of the French Riviera

Located in the Alpes Maritimes the base of the climb rises up from the stunning city of Menton on the Côte d’Azur. You wind your way past some early hairpins and above you is the autostrada road. From here the road to the top leaves the French Riviera behind, heading inland to the summit of 925m / 3034ft. Before you know it you will have climbed well above that autostrada which is always visible on the lower slopes of the climb. On upwards through the small village of St Agnes, the climb begins to transform as you reach the higher elevations. The road here is narrow, almost single lane, and seems to cling precariously to the mountainside. Passing through a small tunnel the scenery on the climb and view back down towards the coast are spectacular. A just reward for those of us who will take much longer than 30minutes to reach the top!

Ride the Madone outside of the peak summer season

Whilst the climb is accessible year-round, if possible it is best to avoid the busier summer months of July and August. Indeed, much of the charm of riding in this area of France is the weather. Again there is a reason so many professional cyclists call this part of France home for their off-season.

Check out our destination guide for the Alpes Maritimes to discover more about the Col de la Madone as well as other rides in the area.

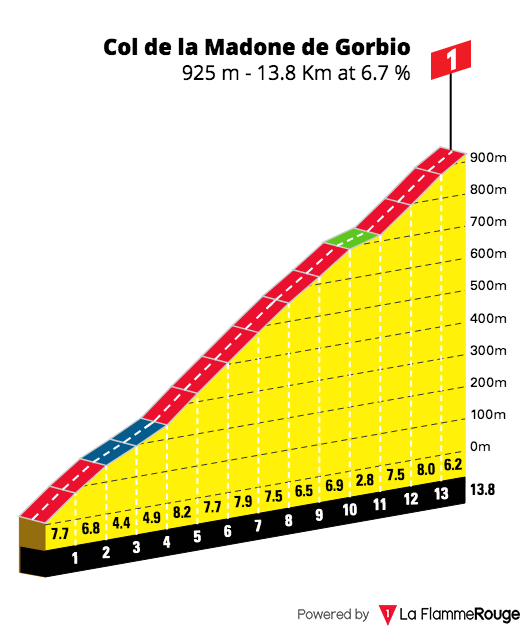

Col de la Madone Climb

Length: 13.8km / 8.6mi

Average Gradient: 6.7%

Starting Point: Menton

Elevation Gain: 921m / 3,022t

Height at Summit: 925m / 3,035ft

7. Col d’Izoard

“You’re not a great champion until you’ve crossed the Col d’Izoard alone in the maillot jaune.”

Louison Bobet – famously led over the Col d’Izoard on three occasions in the Tour de France

Marc Mongenet, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Desert landscape in the high mountains

At an elevation of 2360m / 7743ft, the Col d’Izoard is one of the highest paved mountain passes in Europe. Located in the Hautes Alpes, it is a true iconic climb in the region. A road has existed over this pass since 1710 and the Tour de France first sent riders up over the slopes of the Izoard in 1922. It has been a feature of the race no less than 36 times and owing to its proximity to the Italian border, the climb has also been used on five occasions in the Giro d’Italia.

The most unique characteristic of the Col d’Izoard without a doubt is the rocky, barren slopes leading to the summit. Known as the ‘Casse deserte’ it provides for a very dramatic scene. Huge rock sculptures tower-like cathedrals over the road amongst vast, scree-filled slopes. The landscape certainly adds an extra layer of mystique to this challenging climb.

Memorials to cycling greats

On the southern approach of the climb, just 2kms from the summit is a tribute to two greats of the Tour de France. Fausto Coppi and Louison Bobet each dueled on the slopes of the Izoard multiple times during the 1950s. Indeed, some soil from the slopes of the Izoard was even taken to the grave of Fausto Coppi such was the importance of the climb to his cycling career. At the summit itself, there is also a museum that tells of the exploits of the riders and the history of the climb.

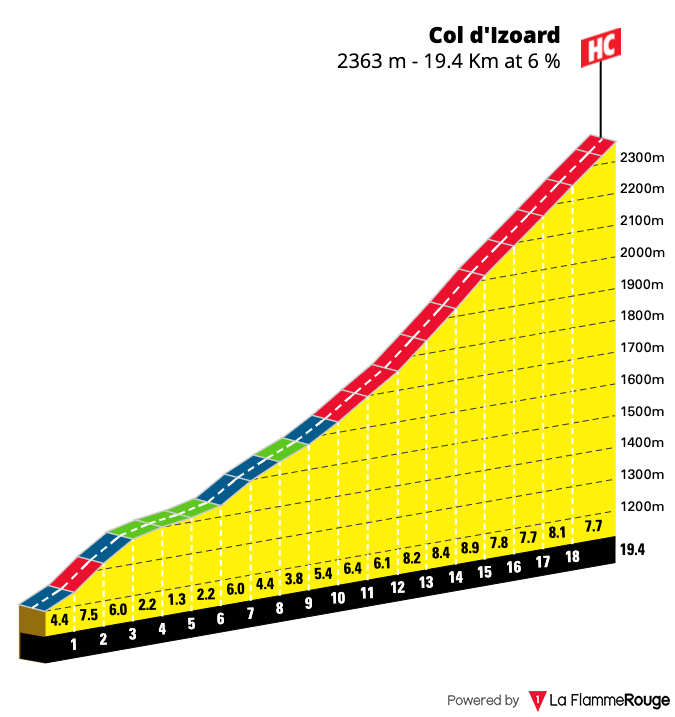

Col d’Izoard – A long climb with steep gradients

You’ll need a great pair of climbing legs to reach the summit of the Col d’Izoard. There are two approaches to the top of the climb and each is quite lengthy. From Guillestre the climb is just under 16km / 10mi long at an average gradient of 6.9%. There are some extremely steep sections on this approach with grades reaching upwards of 14%! From Briançon the climb is slightly longer at 20kms / 12.4mi with an average gradient 5.7%. The maximum gradient on this side reaches 10%. The road to the top is usually open from May through to October depending on snow conditions and thousands of riders take on the challenge of cycling the climb each year. It’s certainly worthy of its legendary status and deserves to be on every cyclist’s bucket list of climbs to ride.

Interested in riding the Col d’Izoard? Our French Alps Destination guide includes details about the climb as well as other rides in the region.

Pline, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

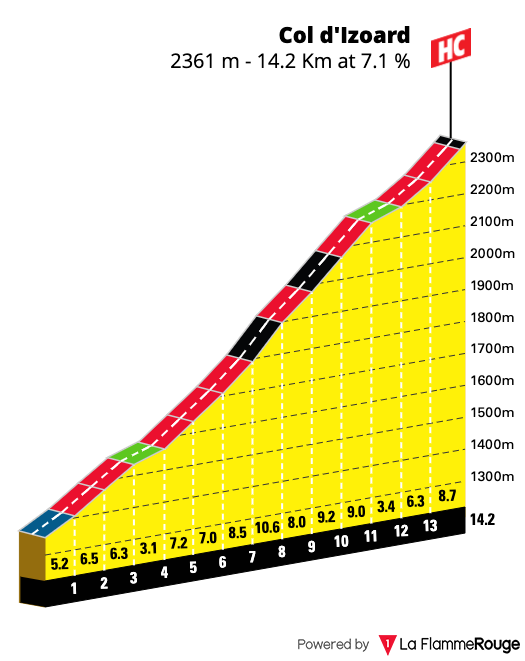

Col d’Izoard Climb (Southern approach)

Length: 14.2km / 8.8mi

Average Gradient: 7.1%

Starting Point: D947 Junction

Elevation Gain: 1,095m / 3,593t

Height at Summit: 2,360m / 7,743ft

Col d’Izoard Climb (Briançon approach)

Length: 19km / 11.8mi

Average Gradient: 6%

Starting Point: Briançon

Elevation Gain: 1,105m / 3,625ft

Height at Summit: 2,360m / 7,743ft

8. Col du Galibier

“You are so, so high up. It’s not like one of these climbs where you look up and see the trees above you, you just go up and it’s like you’re riding into the sky.”

Andy Schleck – winner of the summit stage finish on the Col du Galibier in the 2011 Tour de France

A true mountain great

In 1911 the Tour de France organizers were once again scouting difficult routes. The previous year they successfully sent riders through the high mountain passes in the Pyrenees and now they wanted to outdo themselves once more. The Alps were the next natural point of call. How do you top the summit of the Col du Tourmalet? Send the peloton even higher to the summit of the Col du Galibier! Indeed, the climb of the Col du Galibier is so challenging that only three riders managed to make it to the top without walking! There is a memorial to Henri Desgrange the first director of the Tour de France on the climb. This was apparently his favorite climb in the Alps and he is famously quoted as saying “O, col Bayard, O, Tourmalet… next to Galibier you are worthless.” Now each year there is a Souvenir de Henri Desgrange which is awarded to the first rider to summit the highest point of the Tour de France.

One of the highest paved roads in Europe

The first road to go over the Col du Galibier was little more than a mule track. A one-way high-altitude tunnel was built in 1891 which allowed through access and crossed the mountain at 2556m / 8385ft. This was the crossing point for the 1911 edition of the Tour de France. For many editions, the summit remained at the same point. In 1976 the Col du Galibier tunnel was closed due to safety reasons and a newer route was paved leading up and over the climb. Now riders of the Tour de France are sent over this highest point of the pass, which stands at 2642m / 8668ft of elevation. This makes the climb of the Galibier the eighth highest paved mountain pass in Europe. At this elevation, you are well above the tree line and many riders find the climbing to be much more labored and difficult. Add to this that this new section of road also brings with it the steepest gradient inclines – over 12% – it certainly will add an extra sting to the legs.

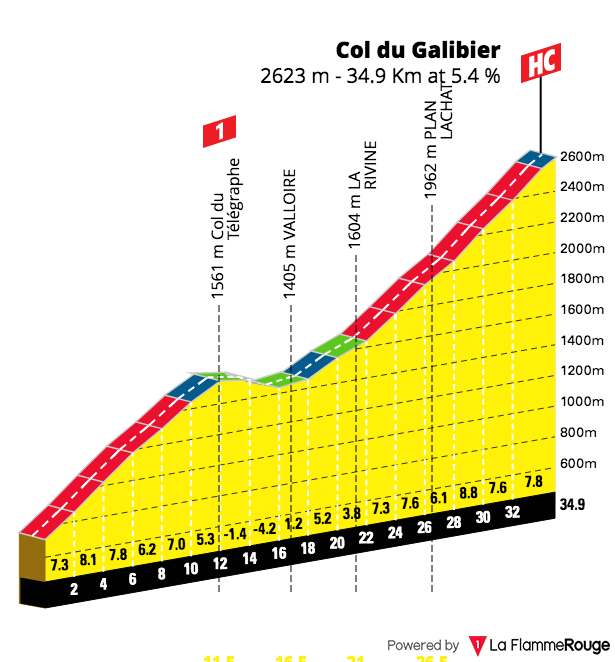

It’s a long way to the top of the Col du Galibier

A lot of the difficulty of cresting the summit of the Galibier has to do with the fact you really need to climb over a mountain pass just to get to the start of the climb. Be it the Col du Lautaret to the South or the Col du Telegraph on the North, whichever approach you take, you will be climbing for well over 30kms to get to the summit of the Galibier. Combined with the elevation this makes for an extra challenging climb.

Tour de France highlights

1998 – Marco Pantani attacks in the freezing rain

Since its first inclusion in the race in 1911, the Col du Galibier has set the scene for some big showdowns. In 1998 during a rain-soaked stage, Marco Pantani broke away on the climb of the Galibier, launching an audacious attack. Jan Ullrich was in the yellow jersey at the time and held what was thought to be a comfortable, race-winning lead. But the combination of the altitude, and the cold miserable weather saw the race win taken away from him. Pantani threw caution to the wind and descended the Galibier with nothing but victory in mind. Ullrich made the poor decision to not put on a rain jacket and subsequently froze on the descent, ultimately losing the race lead and overall victory.

2011 – Andy Schleck’s long-range attack

In 2011 the Col du Galibier was used to host a mountain top finish for the first and only time. Thomas Voeckler was in the yellow jersey, but due to an upcoming time trial, Andy Schleck needed to produce something special to put some time between himself and Cadel Evans. So it was that with over 60kms of racing left on the stage, Schleck launched an attack on the Col d’Izoard, breaking away from the peloton. He then faced the task of the long climb to the summit of Galibier from Briançon into a strong headwind no less. Many doubted his ability to maintain a lead in such conditions but he held on and took the stage victory.

2011 – Short stage sees attacks from Contador and Schleck

The next day the Galibier played host to the riders again, this time cresting the climb through the tunnel from the Northern approach. It was a very short stage, finishing on the slopes of Alpe d’Huez. Early attacks saw both Andy Schleck and Alberto Contador hold a lead over the summit and a high-speed descent set the stage for a thrilling stage finish. Ultimately Cadel Evans would bridge the gap and take overall victory in the 2011 Tour de France with a strong showing in the final time trial in Grenoble. But there can be no doubt the racing on the Col du Galibier over those two stages will be spoken about for years to come.

Want to ride the Col du Galibier? Check out our French Alps destination page for more details about the climb as well as other rides in the region.

Col du Galibier Climb (via St Michel de Maurienne)

Length: 34.9km / 21.6mi

Average Gradient: 6.1%

Starting Point: Saint Michel de Maurienne

Elevation Gain: 2,120m / 6,960t

Height at Summit: 2,642m / 8,668ft

Col du Galibier Climb (via Col du Lautaret Summit)

Length: 8.5km / 5.3mi

Average Gradient: 6.9%

Starting Point: Col du Lautaret Summit

Elevation Gain: 585m / 1,919ft

Height at Summit: 2,642m / 8,668ft

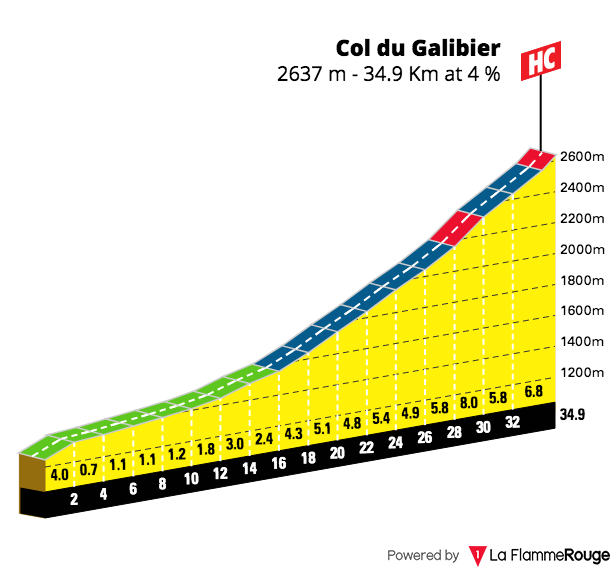

Col du Galibier Climb (via Briançon )

Length: 35km / 21.7mi

Average Gradient: 4%

Starting Point: Briançon

Elevation Gain: 1,388m / 4,533t

Height at Summit: 2,642m / 8,668ft

9. Three Iconic French climbs of the future?

Are these the iconic climbs of the future?

When putting this list together there were a number of climbs that warranted inclusion. They may not quite have the history or come with the pedigree of the climbs listed above, but every iconic climb has to start somewhere and we believe these have the potential to one day be regarded as that.

Col du Portet

First included as a summit finish in the 2018 Tour de France, the Col du Portet now takes the mantle for the highest paved road pass in the Pyrenees. The top of the climb has an elevation of 2215m / 7267 ft and in preparation for the Tours arrival, the final 8 kilometers of the gravel road were sealed. That 2018 Tour stage was only 68kms in length but packed quite a punch with three mountains to overcome and the Colombian Nairo Quintana was the winner of the stage. The Col du Portet will once again feature in the 2021 edition of the race.

Teddy65170, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

The initial kilometers on the climb share the same road as that of Pla d’Adet so be sure to take the right-hand turn when riding this climb for yourself. A series of wide sweeping hairpins lead to the summit and the views back down towards the valley and surrounding mountains are nothing short of breathtaking. To encourage more cyclists to ride the climb in 2020 the local council closed the final section of road off to motorized traffic from Espiaube during the summer months. We really hope this is a trend which will continue each year.

Les Planche de Belles Filles

Located in the Vosges mountains, the climb of the Les Planche de Belles Fils is a relatively recent addition to the Tour de France. First appearing in 2012, the climb has been a fairly regular inclusion ever since and has an uncanny knack for producing Tour de France winners with Chris Froome and Vincenzo Nibali both claiming summit finishes here before going on to win the yellow jersey. Most recently it was the stage for perhaps the most jaw-dropping result with the young cycling talent Tadej Pogačar claiming the yellow jersey with the win on the penultimate individual time trial of the 2020 edition of the race.

Thomas Bresson, CC BY 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Like many famous climbs in France, the road leads to a ski station located at the summit. Whilst only short in length the gradients here are irregular with large parts of the climb well into double digits. The final section of the road has some extremely steep gradients which top out at 20% and will have you gasping for air.

Les Lacets de Montvernier

It may only be a short 3.4km section of road, but every cyclist who sees images of this climb immediately says – where is that? How do I ride it? With no less than eighteen hairpin bends all up, and seventeen of them coming in a section of road just 2kms in length, the serpentine nature of this climb is a wonder. Clinging to the edge of the mountain the narrow road winds its way up towards a small chapel and the mountain village of Montvernier at the summit.

Florian Pépellin, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Once you reach the switchbacks they keep coming thick and fast, almost one every hundred meters or so. Roads of this nature always seem to make the effort to get up them that little bit better and no doubt the 8.5% average gradient will be a little less taxing. The lack of any real traffic also makes it a real treat.

The perspective of the road is best seen from the air – and the Tour de France helicopter has a perfect birds-eye view. So if you don’t own a drone, then the best way to get a view of the road itself is once you reach the top. You need to scramble off the tarmac and into a farm field on the right to get that perspective. Once at the top, the climb continues on to the Col du Chaussy and you can go even further still to the summit of the Col de la Madeleine.

Le Col de la Loze

The Col de la Loze is another new climb located in the French Alps. The Tour de France took the peloton to the summit for the stage 17 finish in 2020. At a height of 2304m / 7559ft, if the elevation doesn’t cause you to be breathless the steep gradients certainly will. The road to the top was created in 2018 linking the ski resorts of Meribel with Courchevel. As you depart from the ski resort of Meribel, the road joins onto a purpose-built cycle path. Yes, that is right – no motorized traffic (apart from e-bikes) is permitted on the climb.

Kuba Turek https://www.horydoly.cz, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

No more than three meters wide in length, the climb of the Col de la Loze goes directly up the side of what in the wintertime is a ski run. Gradients are extremely steep here with kicks of 24% in places. Indeed you may wish you were on an e-bike at times as you grind out the final few kilometers to the top. There is no doubt that this climb will be sought out by thousands of cyclists each year. As for making your way back down – well you will be happy to realize you can descend back down the other side of the mountain on a road that isn’t quite so treacherous!